Growing evidence of a link between football hits and brain injuries has led all 50 states to pass laws aimed at protecting young people from concussions, but a New York lawmaker wants to go even further – banning tackle football.

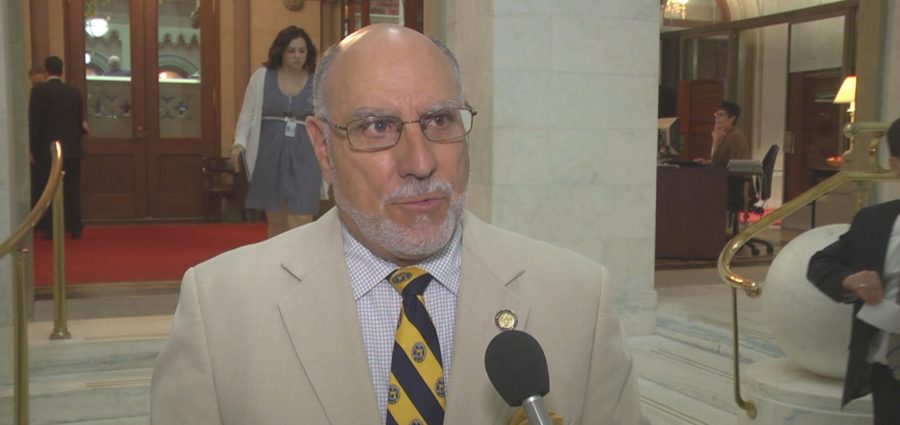

“Football is the only major sport where on every single play, the objective is to violently hit the competition,” said Assemblyman Michael Benedetto, whose measure would bar youth football leagues from allowing anyone 13 or younger to tackle.

And while his bill has gained little support since the Bronx Democrat first introduced it four years ago, with some legislative colleagues bashing it as government overreach, experts say the times may be changing.

Even as the nation gears up to watch the Super Bowl, participation in youth tackle football leagues has dropped nearly 20 percent since 2009. More parents concerned about safety are switching to flag football. And U.S.A. Football, the national governing body for amateur football, is planning to introduce a less violent overhaul of the youth game, with fewer players on the field and rule changes that reduced violent collisions.

“There’s unquestionably a movement afoot, which is wonderful,” said Dr. Robert Cantu, a leading expert on football-related brain injuries and co-director of Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy.

While concussion injuries and deaths of young players make headlines, researchers say the larger danger is repeated sub-concussive hits that linemen absorb on play after play. Several studies have shown that players who started playing tackle football before age 12 have a greater risk of developing memory and cognitive problems later in life.

“Basically it boils down to the fact that a young person’s brain is more vulnerable to injury than is an adult brain,” said Cantu, who has in the past called for no tackle football, no heading in soccer and no full-body-checking in hockey for kids under 14.

State laws intended to prevent head injuries vary, though most require athletes to be removed from a game or practice if a concussion is suspected and be cleared by a medical professional before they can return.

Benedetto said he understands his youth tackling proposal goes well beyond that and will upset football fans who think he is meddling with a beloved pastime.

That would include Republican Sen. Terrence Murphy of Yorktown, a chiropractor who for nearly two decades volunteered at high school football and lacrosse games. He said he’s seen compound fractures, torn ACLs and yes, concussions.

But he said schools have concussion protocols in place and “if I don’t want my son to play football that’s a decision I would make. … It’s another example of big government getting in the way.”

Cantu said legislation wouldn’t be his first choice, either, preferring that “individual organizations see the light and make the change based on parental influence.”

A spokesman for Pop Warner, which bills itself as the nation’s largest youth football program, declined to weigh in on the specifics of Benedetto’s proposal. But Brian Heffron said Pop Warner has already taken steps to reduce concussion risk, such as banning kickoffs for the youngest divisions, requiring coaches to complete a concussion education program and limiting player contact to only 25 percent of practice time.

Ron Ruland, of Cobleskill, a retired teacher who coached high school football for a couple of years, supports Benedetto’s bill but says it is unlikely to pass.

“There is way too much emotion, cultural bias and money invested for there to be a rational discourse on the subject,” he said. “My one hope is that mothers will refuse to sign the permission slips.”