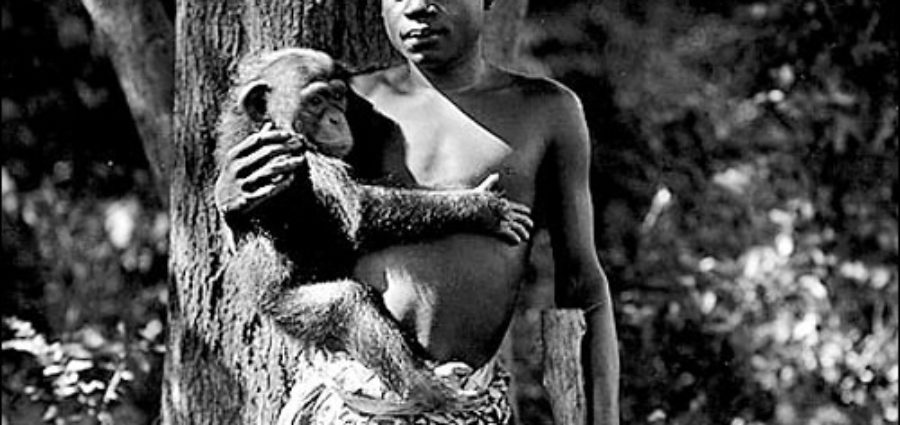

The young black man who arrived at the Bronx Zoo in the summer of 1906 cut a striking figure. Barely dressed, he was carrying a wooden bow, a quiver of arrows, and a chimpanzee. He stood 4’ 11” tall and weighed 103 pounds, and when he smiled, he revealed a set of pointy whittled teeth, like a piranha’s.

At 23, Ota Benga had already lived an equally unusual life to go with his appearance. A member of the Mbuti pygmy tribe, he had hunted elephants, survived a massacre by the Belgian colonial army, had been enslaved and then freed for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. After being escorted to the United States in 1904 by explorer and missionary Samuel Phillips Verner, Benga had more memorable experiences. He danced at Mardi Gras, met Geronimo, and along with other members of his pygmy tribe, was displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair in an anthropological exhibit called “The Permanent Wildmen of the World.” Though he was often referred to as “boy,” Benga had been widowed twice – his first wife was kidnapped by a hostile tribe; his second died from a poisonous snake bite.

By the time Verner brought Benga to New York, the explorer was flat broke. He contacted the director of the Bronx Zoo, William Temple Hornaday, who agreed to temporarily loan Benga an apartment on the grounds. Whether Hornaday had ulterior motives from the start is not clear. An eccentric man who believed he could read the thoughts of his animals, he had many good qualities. Namely, he was one of the first to encourage the display of animals in natural settings rather than small cages. But Hornaday also believed that pygmies were a sub-race, closer to animals than humans. And before long, he was displaying Ota Benga at his zoo in what he called an “intriguing exhibit.” The display was intended to promote the contemporary concepts of human evolution and scientific racism.

“Is that a man?”

In his first few weeks, Benga wandered around the grounds of the zoo freely. But soon, Hornaday had his zookeepers urge Benga to play with the orangutan in its enclosure. Crowds gathered to watch. Next the zookeepers convinced Benga to use his bow and arrow to shoot targets, along with the occasional squirrel or rat. They also scattered some stray bones around the enclosure to foster the idea of Benga being a savage. Finally, they cajoled Benga into rushing the bars of the orangutan’s cage, and baring his sharp teeth at the patrons. Kids were terrified. Some adults were too, though more of them were just plain curious about Benga. “Is that a man?” one visitor asked.

Hornaday posted a sign in the Monkey House outside the cage with Benga’s height and weight and how he was acquired. It read:

The African Pigmy, “Ota Benga.”

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight, 103 pounds. Brought from the

Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Cen-

tral Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Ex-

hibited each afternoon during September.

If Hornaday’s attitude towards his new acquisition needed further elaboration, it was summed up in the odd tone of an article he wrote for the zoological society’s bulletin:

“Ota Benga is a well-developed little man, with a good head, bright eyes and a pleasing countenance. He is not hairy, and is not covered by the downy fell described by some explorers… He is happiest when at work, making something with his hands.”

Thanks to a piece in the New York Times, word of the exhibit spread. “We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people,” the Times wrote, “and then we bring one here to brutalize him.” Though in an editorial, The Times also said Benga “is probably enjoying himself as well as he could anywhere in his country, and it is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation he is suffering. …

The pygmies … are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place … from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.”

Soon a group of black clergymen was leading protests around the city. After a threat of legal action, Benga was let out of the cage, and once again allowed to roam around the grounds of the zoo. But by then he was a celebrity, and the zoo was attracting up to 40,000 visitors a day, many of whom followed Benga wherever he went, jeering and laughing at him. Benga spoke no English, so couldn’t express his frustration. Instead he lashed out, wounding a few visitors with his bow and arrow, and threatening a zookeeper with a knife.

After Benga left the Bronx Zoo, several institutions, including the Virginia Theological Seminary, took him in. He eventually got a job at a tobacco factory in Lynchburg, Virginia, but grew depressed and homesick. In 1916, he committed suicide by shooting himself with a pistol at the age of 32.

Later in life, William Hornaday became known for his efforts in saving the American bison and the Alaskan fur seal from extinction. In 1992, Samuel Verner’s grandson Phillip Bradford co-wrote a book about Benga’s life, Ota Benga: The Pygmy In The Zoo.