For a decade the government turned its back as the Bronx burned. Photographer Ricky Flores captured his home city’s enduring spirit as its residents found hope in a new art movement – hip hop.

The South Bronx became infamous during Game 2 of the 1977 World Series, when newscaster Howard Cosell noticed a nearby abandoned school engulfed in flames and not a fire truck in sight, uttering his legendary phrase, “There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”

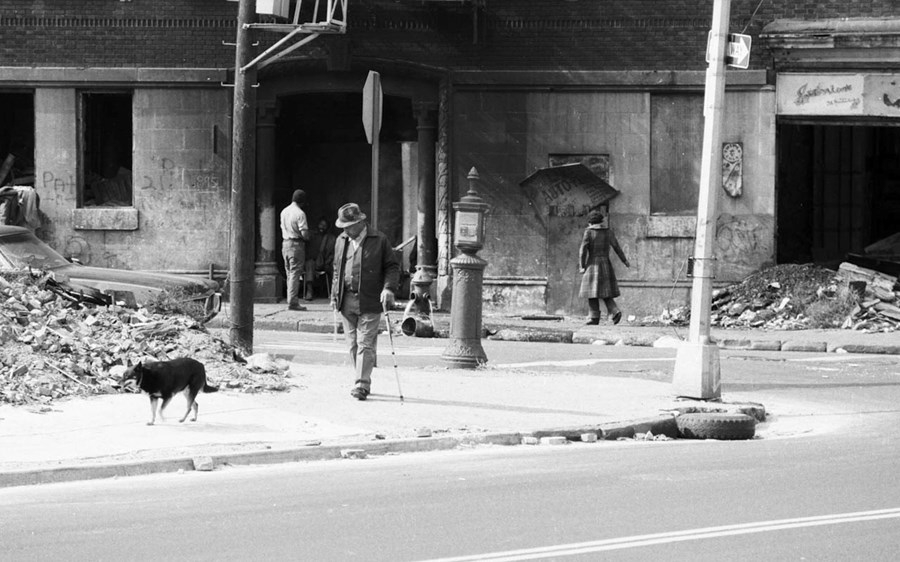

Bronx had been burning throughout the 70s, in a massive series of fires set by arsonists working on behalf of landlords who knew they could collect more money from insurance fraud than they could from rent. From 1970 to 1980, more than 97 per cent of seven census tracts in the South Bronx had been lost to fire and abandonment, turning the once majestic neighborhood into blocks of rubble resembling a war zone. Yet, through it all, the people of the Bronx persevered.

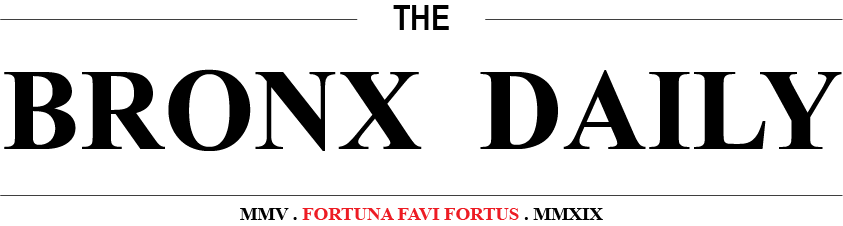

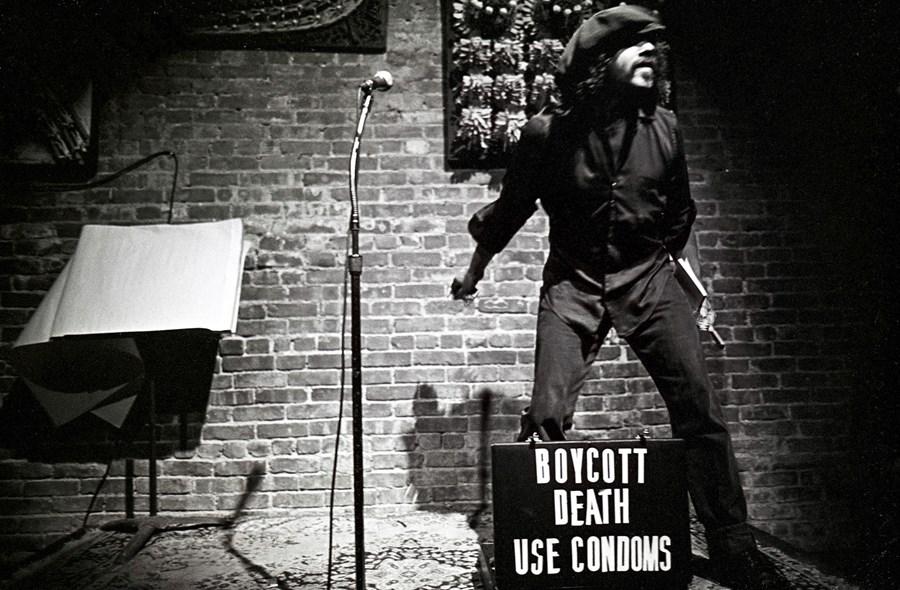

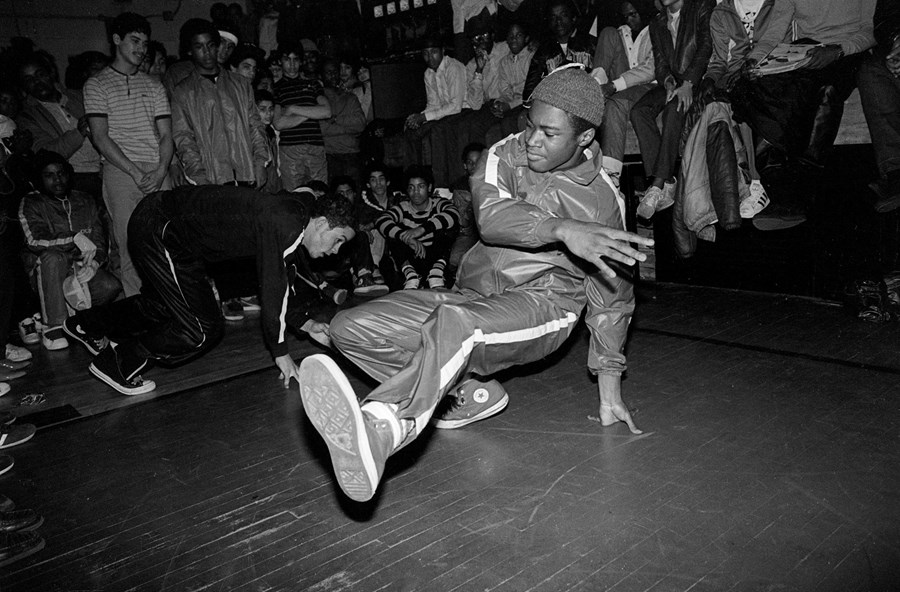

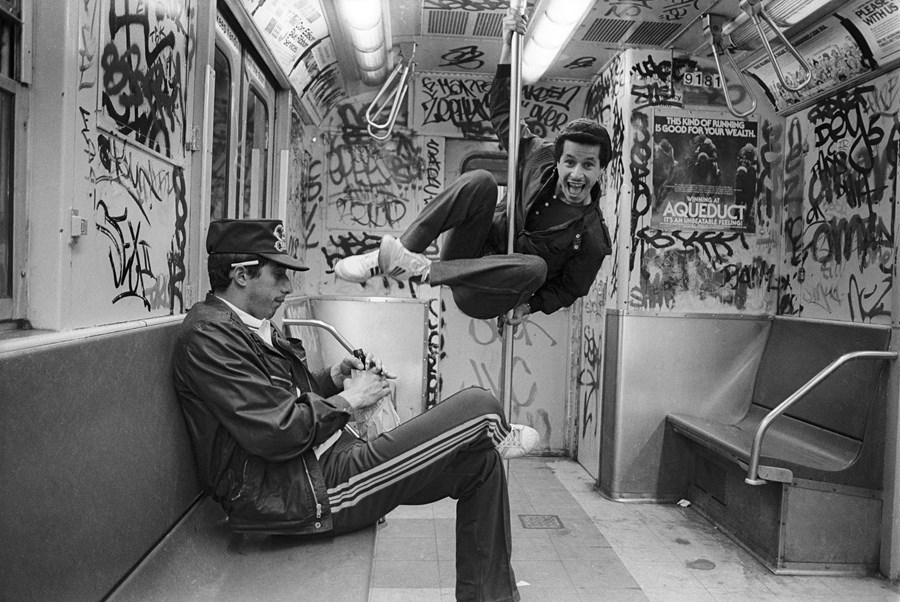

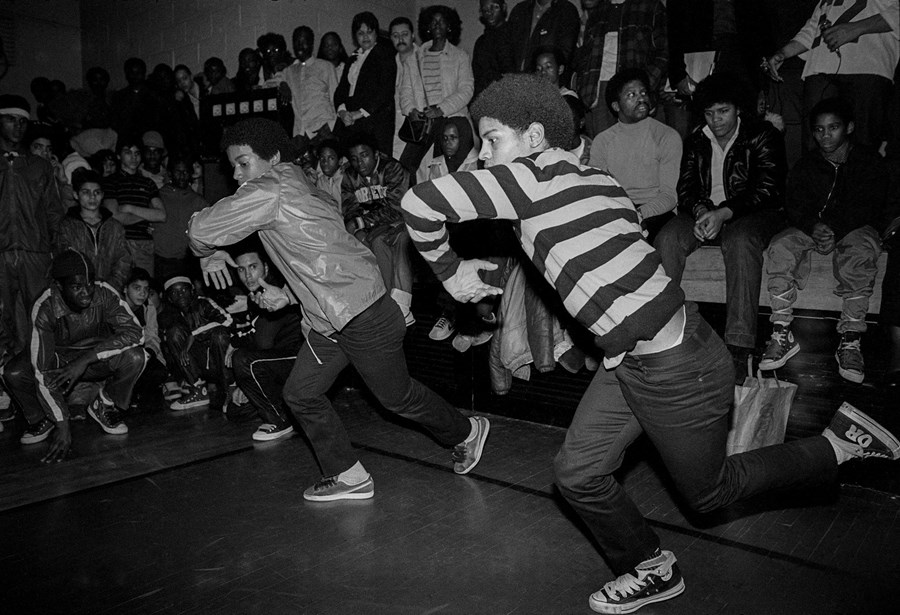

The era was ruled by the do-it-yourself ethos, because under a governmental policy of “benign neglect” (systemic racism that denied basic services to Black and Latinx neighborhoods), it was understood if you didn’t do it, no one would. Hip hop was born out of the fires, the poverty, and the despair, as a new generation of youth invented a brand new art form using nothing but pure ingenuity.

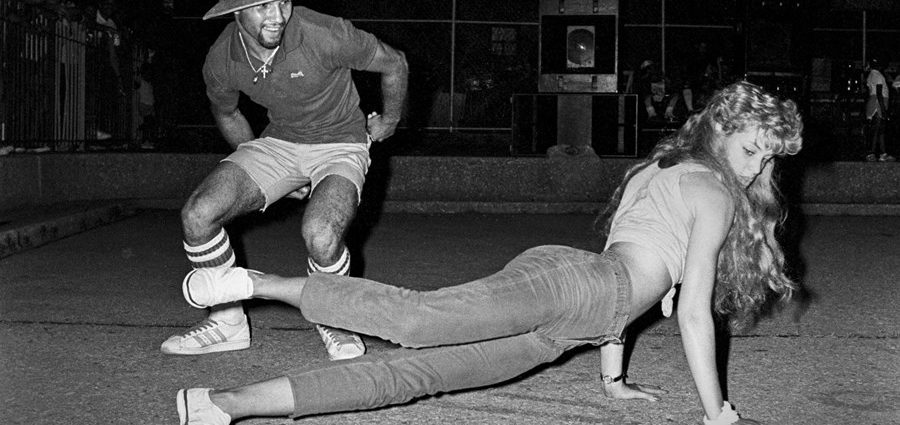

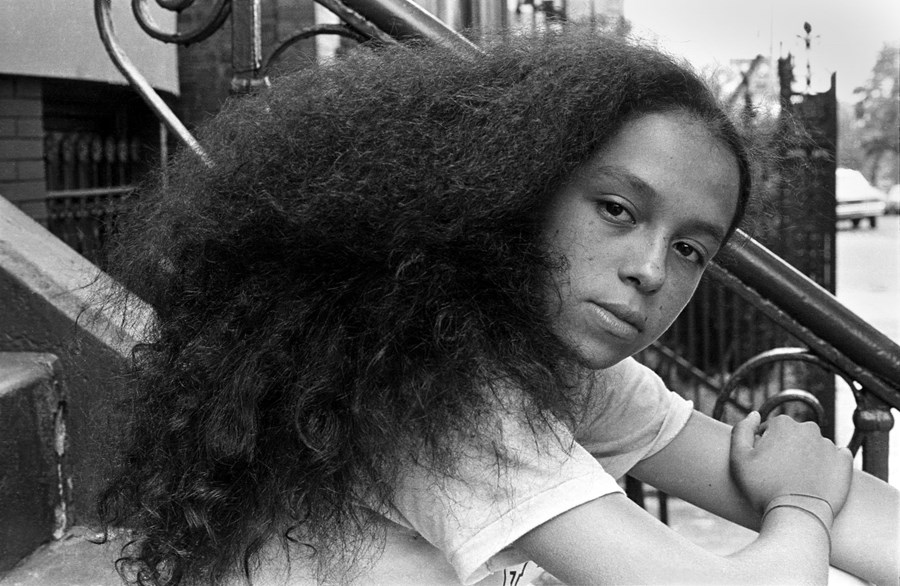

South Bronx native Ricky Flores began taking photographs as a high school senior in high school in 1980, shooting pictures of his friends and his neighborhood. His photographs capture the South Bronx as it was, a place filled with beauty amidst the rubble. He began studying with Mel Rosenthal, one of the most renowned photographers of the South Bronx, and realised he had a responsibility to document his community as an insider.

While outsiders, working for the mainstream media or Hollywood, would come in and create an image of the Bronx as the worst borough in New York City, Flores photographed the community as he knew them to be: a warm, creative, dynamic, resilient, and strong. Flores gives Dazed an inside look at growing up in the South Bronx.

“Hip hop today is a commercial manifestation born from the real struggle of seeking and living life in community forgotten by a nation. Early Hip hop was taking what was made available and transforming it into something that spoke to us” – Ricky Flores

Tell us about the hip hop scene as it was when you were coming up.

Ricky Flores: It didn’t exist back then but it was being created. Our scene was heavily influenced by Motown, R&B, rock, disco and salsa. Those dance years were more impacted by the extended LPs such as Kraftwerk’s “Trans Europe Express,” Emmanual “Manu” Dibango’s “Soul Makossa,” and Donna Summer, to name a few, which were remixed by early DJs for dancing. Everyone wanted to be a DJ but not everyone had the wherewithal to get the equipment. That’s where the boombox came in: a cheaper solution, which allowed you to tape your favorite jams off the radio and play those anytime you wanted.

Was hip hop as monolithic as the commercial thing that it had become today?

Ricky Flores: Nah. Hip hop today is a commercial manifestation born from the real struggle of seeking and living life in community forgotten by a nation. Early Hip hop was taking what was made available and transforming it into something that spoke to us. It was a wild and spontaneous thing that was created on the fly.

The Fort Apache police precinct was in Longwood. What did you think when the Hollywood movie Fort Apache, The Bronx came out?

Ricky Flores: I think we kept the name but tossed the movie. I mean there is a certain street cred that came with saying you were from Fort Apache. We understood how the world viewed us and attempted to build a nice racist stereotype of who they thought we were. In nothing else, we understood publicity; history has proven that because folks are still hungry for that history.

The reality we knew was quite different; our community was poor and working class with a powerful work ethic. It was not an uncommon sight to see people streaming down the block to the train station and getting on the subway heading out to work. To have parents sacrifice to send children off to Catholic school or putting food on the table by whatever means necessary. It wasn’t uncommon for us to have summer jobs or working with local merchants. Reality on the streets was mundane as well as fantastic.

Can you talk about the fires? What was it like living in that environment?

Ricky Flores: It is a traumatic experience that has had a lasting generational impact. You simply cannot destroy a community, particularly, during rising health crisis, which then was the start of the Aids, cut health services, and scatter people to the wind without consequence. Compound all those issues with poverty and racism and you are talking about impacting generations of people.

For myself, the past has come back to me in startling and unexpected ways that have had a profound emotional impact. My mum started exhibiting schizophrenia in my early teens; that left me pretty much to my own devices growing up. My father had died when I was five and my stepfather had little control over me at the time. On top of that were the language barriers they faced when it came to seeking medical help for her. I had no choice but to become a caretaker at a very young age. I’m talking starting around nine or 10-years-old when this all started until the day she died. I can’t count how many times we went to all those social services appointments, seeking financial and medical help, where I acted as a translator and dealing with those workers who were downright nasty when we showed up. Those were my early lessons in what racism felt like during those years.

Add to all that was wondering whether your home would burn down. A very real fear when you watch building after building either being abandoned or burned to the ground. I became a light sleeper and have been woken many times simply by the throbbing of the engines of a fire truck outside my apartment building. I also got adept at breaking down neighbors’ doors when we suspected there might be a fire behind when we got no response after we knocked and smelled smoke. It’s a hell of a skill set for a teen to learn how to do in order to keep a roof over our heads.

“It’s about the activists, the working families, the community groups, the everyday people of all races and backgrounds who came together and made a stand when the city, the state and a nation, turned their backs on our community” – Ricky Flores

How did you get into photography?

Ricky Flores: I had received a small inheritance from my father and I was influenced by a friend who was getting into photography. I bought a Pentax K-1000 with a 50mm 2.8 lens and a cheap flash all neatly contained in a fake leather camera bag and I never looked back. I loved the way that camera felt in my hand and that satisfying click when you hit the shutter button. I was broke as hell so I had to figure out ways to make money to keep me in film.

Do you think photography helped you deal with the trauma and loss?

Ricky Flores: It did help because what started out as a hobby became a mission to document as much as possible how I understood what was happening back then. It is by no means a complete picture of everything that has happened but it sure as hell a very comprehensive one of what I saw. It is a visual diary of my life and of those people that I grew up with, many of them still alive. It is visual proof that not only we lived through all that but thrived. It is also a reminder that not all of us made it and that their lives did have meaning and had a lasting impact on the world.

I take comfort in that. I think many of my friends get comfort from remembering how powerful we were back then and that every day was a new adventure. Not to paint too rosy a picture, the crack epidemic in the late 80s and early 90s was the final blow to many families, but there was a moment there, between the gangs and the fire years and the crack epidemic where the streets were ours, the summers warm and the nights were long, filled with music and laughter. Those days where we would watch couples dance on a street corner, those glorious moments of peace at night on the roof listening to music.

What do you think is the biggest misperception of the Bronx? How do you think your photos counter – or better yet, obliterate – the narratives out there?

Ricky Flores: I think people need to move past the commercialised cultural elements born from those early days of the South Bronx. The story is so much richer and deeper than that. It’s about the activists, the working families, the community groups, the everyday people of all races and backgrounds who came together and made a stand when the city, the state and a nation, turned their backs on our community. It is there, during that time, where our cries of protest were born, that is still being heard to this very day around the world. In the sharing of that history, we hope that not only would they learn more about those days but also pay more attention to what is taking place in their own cities and towns. The lesson is a clear and simple one, if it happened to us, it can happen to you in the United States of America.